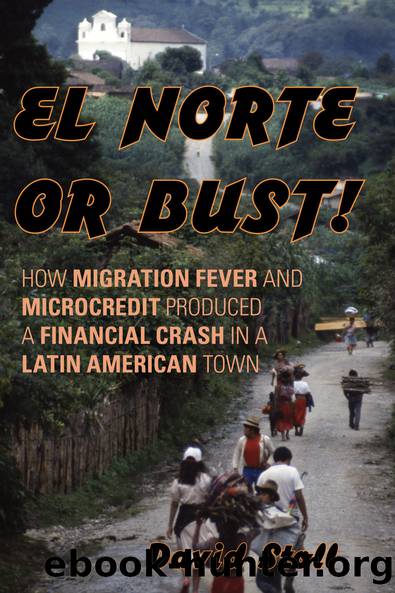

El Norte or Bust! by Stoll David;

Author:Stoll, David; [Stoll, David]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers

Published: 2012-08-15T00:00:00+00:00

Chapter Six

Projects and Their PenumbraâSwindles

Missionaries, guerrillas, soldiers, and politicians have all, in their different ways, promised Nebajenses the rewards of modernity. When such benefits actually arrive, it is usually in the form of a projectâtypically a projection by outsiders of how Nebaj could become a better place if only the Nebajenses would organize in a certain way to carry out certain improvements. Since Catholic and Protestant missionaries introduced this model in the 1950s, the Nebajenses have taken to it with vigor and ingenuity. They have organized themselves in many waysâas Christians, revolutionaries, voters, and Mayas, as women, violence victims, and solidarity groups. Their hopes in projects reached an apogee with the 1996 peace accords. Thanks in no small measure to projects, most Nebajenses are now better shod, housed, doctored, and schooled than before. But they place fewer hopes in projects, and one of the reasons is the difficulty of distinguishing between projects and swindles.

This is not just a challenge for illiterate peasants. In cooperation with the U.S. Agency for International Development, or so she thought, an experienced Ixil organizer collected Q25 quotas from women to start a weaving cooperative. She added Q800 of her own and delivered Q2,500 ($320) to a Guatemalan employee of USAID. He was never heard from again. When she asked USAID, it informed her that he was no longer an employee. A former mayor of Nebaj told me how, in 1990, when fifty quetzals was a substantial sum, a Kâicheâ aid coordinator arrived in town announcing a project to supply roofing and other building materials. The mayor and 150 other Nebajenses each handed over Q50. On the appointed day, they chartered vehicles to Tecpán, Chimaltenango, to take delivery. Here they found themselves in a crowd of five thousand people. The aid coordinator never showed up.

Swindles such as these are a mirror image of village-level aid projects, the kind that stress participation, and the way they resemble such projects is not very flattering. In both projects and scams, as Jan and Diane Rus have observed in southern Mexico, a central role is played by the promotor or intermediaryâthe villager who signs up neighbors for free or low-cost benefits. To receive the benefit, villagers must attend meetings and provide unpaid labor. Most attractively for swindlers, villagers must also pay aportes, or contributions, to demonstrate that they are not just lining up to receive a handout.1 Other parallels include

the largesse that comes from a distant and mysterious source;

the rhetoric of democracy (âgrassrootsâ in English, popular in Spanish), even though donors have made key decisions beforehand and will prevail in case of disagreement; and

the rhetoric of community, even though the most aggressive and mendacious individuals collect disproportionate rewards and are rarely punished.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Accounting | Economics |

| Exports & Imports | Foreign Exchange |

| Global Marketing | Globalization |

| Islamic Banking & Finance |

The Meaning of the Library by unknow(2384)

Six Billion Shoppers by Porter Erisman(2224)

Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty by Daron Acemoglu & James Robinson(2170)

No Time to Say Goodbye(1996)

Red Notice by Bill Browder(1924)

The Economist [T6, 22 Thg9 2017] by The Economist(1843)

Currency Trading For Dummies by Brian Dolan(1788)

Thank You for Being Late by Thomas L. Friedman(1675)

Bitcoin: The Ultimate Guide to the World of Bitcoin, Bitcoin Mining, Bitcoin Investing, Blockchain Technology, Cryptocurrency (2nd Edition) by Ikuya Takashima(1611)

Amazon FBA: Amazon FBA Blackbook: Everything You Need To Know to Start Your Amazon Business Empire (Amazon Empire, FBA Mastery) by John Fisher(1491)

Coffee: From Bean to Barista by Robert W. Thurston(1418)

The Future Is Asian by Parag Khanna(1397)

The Great Economists by Linda Yueh(1388)

Capitalism Without Capital: The Rise of the Intangible Economy by Jonathan Haskel(1337)

Pocket World in Figures 2018 by The Economist(1325)

How Money Got Free: Bitcoin and the Fight for the Future of Finance by Brian Patrick Eha(1322)

Grave New World by Stephen D. King(1314)

The Sex Business by Economist(1279)

Cultural Intelligence by David C. Thomas(1201)